Protect the tatara flame and experience the culture of iron.

WAKOU MUSEUM

Wakou Museum is dedicated to the history and development of the tatara furnace, a tool for smelting iron and steel that was developed in Japan and used widely in this region.

Before exploring the exhibits, visitors are encouraged to first stop by the museum theater and view a 15-minute film explaining the tatara ironmaking process. This short documentary shows the smelting operation at Nitt?ho Tatara, the only ironworks in the world where steel is smelted using a clay tatara furnace. The film shows how simple materials, such as clay, iron sand, and charcoal, are used to produce a high-grade steel called tamahagane. English subtitles are available upon request.

The exhibit rooms on the first and second floors present the history of ironworking innovation in the region.

The technology for smelting iron ore arrived in Japan sometime in the late sixth century, and it was soon adapted for smelting iron sand, which was more readily available. Seeking to maximize both output and quality, ironworkers found large-scale sources of raw materials and designed more powerful bellows and furnaces. Later advancements in modern steelmaking in the twentieth century gave rise to the creation of Yasugi Specialty Steel, a new variety of steel renowned for its hardness and durability that is still produced locally. Yasugi Steel is thus the most recent chapter in this centuries-long history.

Tatara Ironmaking?

Exhibit Room 1 provides an overview of the tatara ironmaking process. It includes explanations of the production cycle, tools that were used at ironworks in the region, samples of the iron and steel produced there, and a full-scale model of a late nineteenth-century furnace.

The tatara method is unique to Japan and differs from other contemporary smelting methods in its use of iron sand and wood charcoal instead of iron ore and coal (or other non-renewable fuel sources). Although the tools and equipment have changed, the fundamental principles of the tatara method have remained the same since the late sixth century.

The ironmaking industry thrived in the mountainous Ch?goku region (Hiroshima, Okayama, Shimane, Tottori, and Yamaguchi Prefectures), where high-quality iron sand was readily available. As craftsmen developed more efficient smelting techniques, small, temporary ironmaking operations were replaced by large, permanent operations run by entire villages. By the early 1900s, this accumulated expertise had allowed the region to become the largest producer of iron and steel in the country, laying the foundations for the region’s modern-day steel industry.

Gathering Iron Sand:

Kanna-Nagashi

The iron sand used in the smelting process was gathered by sifting riverbeds for sediment that had accumulated naturally. However, collecting iron sand in this manner was a time-consuming process. By the late seventeenth century, a more effective technique called kanna-nagashi had been adopted throughout the region.

Instead of waiting for erosion to occur naturally, workers dug into exposed cliffsides by hand. The crushed rock fell into manmade canals that were dug alongside the exposed cliffs and was carried

downstream to a sorting station at the foot of the mountain.

The sorting station comprised a series of four terraced pools that separated the heavier iron sand from the rest of the sediment. Iron sand sank to the bottom of the pools, while everything else flowed out through openings between them.

These dioramas depict several scenes of kanna-nagashi on a snowy winter day. This method was not permitted during the growing season to prevent sediment from damaging rice fields downstream.

harcoal and

Forest Management

Charcoal is vital to the tatara ironmaking process. It acts as both a fuel and a reducing agent: the burning of charcoal releases carbon dioxide that reacts with and removes oxygen atoms from the iron sand, leaving behind elemental iron.

Oak, pine, and beech wood was used to make charcoal for tatara furnaces. Wood was taken primarily from trees that were at least 30 years old; by that age, they had already produced new generations of saplings, and their growth had begun to slow.

Charcoal is made by heating wood past the kindling point in an oxygen-deprived environment to prevent it from catching fire. By heating the wood at different temperatures and

changing the duration for which it is “cooked,” it is possible to change the characteristics of the charcoal. The charcoal for tatara furnaces still contains a certain amount of organic matter, which burns faster and at a higher temperature, creating the temperatures necessary to smelt iron and steel.

At the height of ironmaking in the region, the average tatara furnace operated 60 times per year, annually consuming roughly 810 metric tons of charcoal. This meant that each furnace needed nearly 60 hectares of forest to supply it with charcoal. The ironworks owner was responsible for managing the forest so that fuel did not run out.

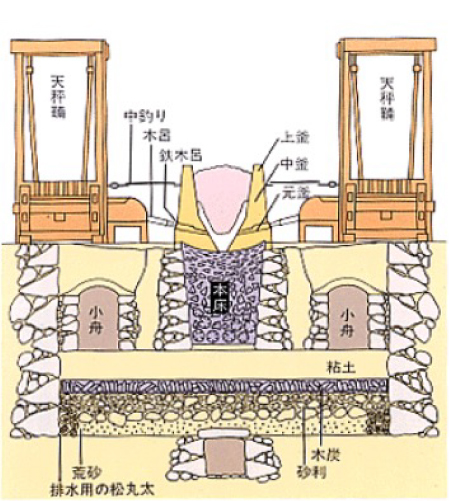

Underground Structure of a

Tatara Furnace

These dioramas show the process of building the underground structure of a tatara furnace. As larger and larger furnaces were developed, it became more challenging to maintain the high temperatures needed to smelt iron and steel. The furnace’s underground section was devised to insulate the hearth and prevent heat from escaping. The basic design emerged in the fifteenth century, but the advanced version shown here was adopted in the 1700s.

To create the underground structure, workers first dug a pit between 3 and 5 meters deep that spanned a large area inside the takadono workshop. They built a narrow, stone-lined tunnel along the bottom of the pit to allow drainage, then covered the bottom with layers of gravel, clay, and charcoal. These components

helped prevent underground moisture from reaching the furnace.

Next, workers constructed three stone-lined compartments: a deep trench in the center (directly below where the hearth would be built) with one smaller compartment on either side. These compartments were packed with wood, which was then burned to dry out the surrounding earth.

Once the fires died out, the trench was filled with charcoal and compacted ash to create a moisture barrier. The two smaller compartments were left empty to trap some of the escaping heat. Finally, workers filled in the remaining parts of the pit with clay to create a flat surface for the hearth and bellows.

Operating a

Tatara Furnace

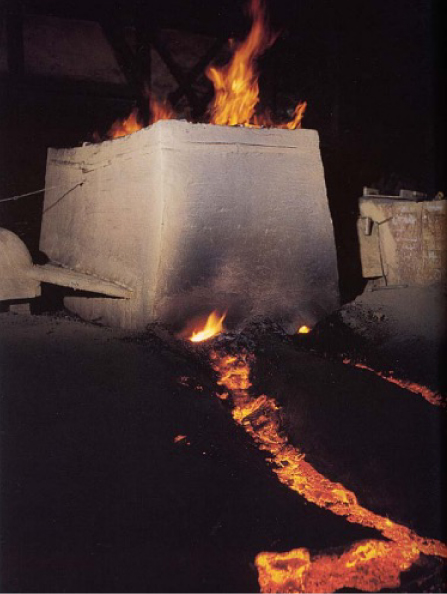

Tatara furnaces can be operated using two different methods: direct smelting and indirect smelting. The direct method creates a porous mass of iron and steel, called a kera, which is formed at the bottom of the furnace. The indirect method creates lower-grade pig iron, which flows out through channels at the base of the furnace.

Direct smelting is employed at Nitt?ho Tatara, a local ironworks that revived the tatara method. Each operation is a continuous process that lasts three days and three nights. While a crew of workers maintains the supply of raw materials in the workshop, the murage (foreman) and his assistant add layers of iron sand and charcoal to the furnace every 30 minutes or so.

The exact amounts of iron sand and charcoal consumed in a single operation of the furnace differ each time. The murage must judge how much to add by listening to the sound of the furnace and observing the state of the kera through small holes in the furnace near the air pipes. On average, Nitt?ho Tatara uses 10 metric tons of iron sand and 12 metric tons of charcoal to produce a kera weighing 3 metric tons.

Faith in Kanayago,

Kami of Tatara Ironmaking

Kanayago Jinja Shrine is the foremost shrine dedicated to Kanayago, the guardian kami deity of tatara ironworking. By the late 1700s, faith in the deity had spread widely among ironworking communities in the Ch?goku region (now Hiroshima, Okayama, Shimane, Tottori, and Yamaguchi Prefectures). The documents displayed here are records of donations made in 1791, 1807, and 1819 for repairs to the shrine.

According to an eighteenth-century text called Tetsuzan hisho (Secret records of the Iron Mountains), Kanayago descended to Harima Province (now Hyogo Prefecture) from the heavenly realm of the kami. Riding on the back of a white heron, she searched the region for a suitable residence and alighted on a katsura tree

in the mountains roughly 35 kilometers southwest of where Wakou Museum now stands. A man named Abe Masashige was hunting in the mountains, and he was startled to see Kanayago descend from the heavens. Kanayago ordered Abe to build a shrine, and when it was complete, she taught him how to make iron using the tatara method. The shrine now stands in the Hirose district of Yasugi.

Kanayago is frequently described as a particularly finicky deity who is unhappy with her own appearance and jealous of other women. In fact, women were often prohibited from approaching the furnace during the smelting operation to avoid angering Kanayago. She is sometimes depicted riding a fox.

Life in Sannai Village

Sannai was a mountain village that was made up of workplaces and homes of people engaged in Tatara iron-making. Sannai was chosen because it was possible to secure huge quantities of charcoal and iron sand as raw materials, which were essential for tatara operations, as well as water for daily use, and it was also convenient for transporting the iron and steel produced and carrying in food.

Sannai consisted of the following buildings and facilities, which can be broadly divided into iron-making facilities and residential buildings.

The most important location within Sannai was the Takadono, where a tatara furnace was installed to make iron (smelt). An iron pond (kanaike), where the crude steel drawn from the Takadono was cooled. Oudouba, where the crude steel was crushed. Shoudouba, where the crushed crude steel was divided into smaller pieces. Kanetsukuri (steel making), where the crushed steel was sorted. Additionally, many large forges were built alongside tatara iron-making, as these facilities were essential to the process, and where wrought iron was produced by heating and forging pig iron other than steel and inadequately smelted small crude steel, to remove impurities, reduce carbon content, and homogenize the wrought iron. In addition, there was an iron warehouse to store iron and steel before shipment, a charcoal shed to store charcoal, and a rice warehouse to store food.

In addition, there was a washing area where the iron sand was finally scoured, and Motokoya that served as an office that controlled all of Sannai. The shrine of Kanayago-kami, the common object of worship for people engaged in tatara, and the densely built houses where craftsmen and their families lived, made up the village of Sannai. It also included people dedicated to burning tatara charcoal, and the population there was said to have been between 100 and 200 people.

Sannai maintained its own extraterritorial autonomy separate from the farming villages called Jige, but life there was not one of affluence.

Among the craftsmen, those who could be called engineers were Murage (chief engineer,) Sumisaka (assistant chief engineer), Daiku (carpenters), and Sage (craftsmen who made base metal), and they were given a stipend, but others were paid only enough to guarantee a minimum living, so many of them are considered to have lived on advances from their wages. Many of the Banko, who blew bellows, were homeless wanderers or penniless men, so Sannai village elders imposed strict regulations to prevent friction with villagers. Sannai had its own police powers, and it seems enforced some very strict measures, but without these people, the demand for iron and steel in pre-modern Japan could not have been met.

和鋼博物館 友の会

たたら製鉄を起点とする歴史・産業・文化に関する知識を高めるとともに、会員相互の親睦を図りながら和鋼博物館が行う活動を支援し、その普及発展に寄与することを目的として活動しています。